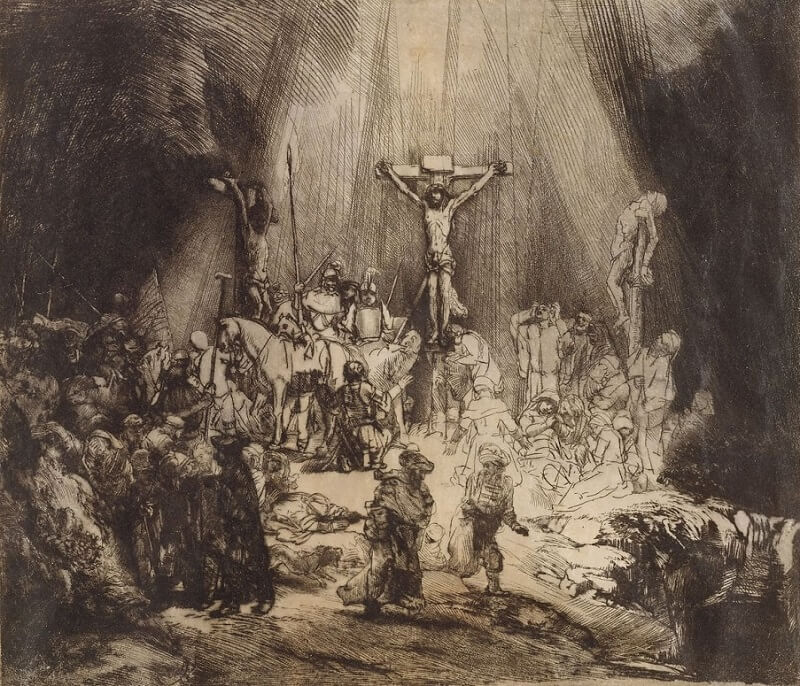

The Three Crosses, 1653 by Rembrandt

The subject of The Three Crosses is Jesus Christ on the cross, flanked by the two thieves who were crucified with him, and the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus, weeping and supported by the Evangelist. Roman soldiers on horseback, along with grieving citizens, surround the crosses. A beam of light, representing God's light from heaven, pierces the darkened sky to envelope the crucified figure of Christ.

The Three Crosses does not allow for dramatic contrasts of light and shade, known as chiaroscuro. Rembrandt produced the work in four stages, increasing the effects of the light and shade contrasts at each stage. Etching and drypoint are labor-intensive processes and one of the early forms of printmaking.

The Three Crosses, one of Rembrandt's finest works in any medium, represents the culmination of his virtuosity as a printmaker. He drew on the copperplate entirely in drypoint which allowed him to fully exploit the velvety areas of burr raised by the drypoint tool as it cut into the copper. When Rembrandt created this impression, he deliberately left ink on the printing plate; it lightly veils the figures standing at the foot of the cross on the right; a thicker layer almost completely covers the bushes along the right edge.

By creatively inking the copperplate, Rembrandt in a certain sense painted each impression. Each time he printed the copperplate he created a unique work. He further varied impressions by printing them on different supports; this impression is printed on vellum, which infuses the composition with a warm light. Vellum, less absorbent than paper, holds ink on the surface, softening lines and enhancing the richness of entire effect.