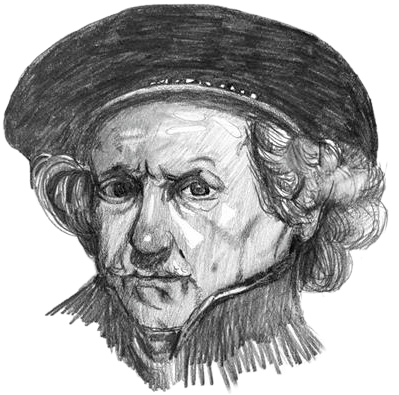

Self Portrait, 1658 by Rembrandt van Rijn

In his youth Rembrandt had decked out himself and his models with the most fantastic costumes, and from the inventory of his possessions it appears that he was also an enthusiastic collector of these party props. Sometimes it is plain

what he means to say with these brilliantly dressed up figures, and who they represent - a prophet, an Old Testament character, an apostle, or a Roman goddess. But more often the exact meaning of these fanciful costumes is uncertain.

The question is even more difficult in the case of a self-portrait. Is it indeed a self-portrait in the literal sense of the word, or did Rembrandt want to depict some specific character - a philosopher, a saint, a historical figure -

but used his own likeness to do so? Sometimes his characters look as if they have escaped from a theatrical performance, and the theatre of that time has often been searched for parallels to Rembrandt's paintings - mostly in vain, since

Rembrandt is not generous with clues, and also because information on seventeenth-century theatre is, at least as far as costume is concerned, rather limited.

This self-portrait is an 'unsolved' picture. It shows a princely figure; the sturdy body is wrapped in a yellow-gold garment that looks as if it has been made for a grand occasion, with a loosely wound red sash with a finely worked

tassel, a gold-embroidered collar, and a white kerchief round his throat. Over all is a wide cloak of fur or velvet. His right hand rests on the arm of a chair; in his left hand the man holds a cane (a sceptre?) with a shining knob on

top, his wrist resting on the other arm of the chair. The cap with its scalloped edge had been one of Rembrandt's favourite attributes since his self-portrait of 1640 in Italian style.

The portrait is the more impressive because the man is portrayed three-quarter length and the observer has to look up at him. His cap throws a shadow on the forehead, but the fierce brown eyes, unmistakably Rembrandt's eyes, look

straight at the observer; that wide nose, tight mouth - it is unmistakably Rembrandt.

Rembrandt's personal circumstances that year seem to have been completely the opposite of those shown in the portrait. In 1658 the third sale of his property took place, and all his possessions, his house, his furniture, his works, his

art collection, were now sold. But the proceeds, some 17,000 guilders, were not enough to satisfy his creditors. It was plain: Rembrandt would have to leave his fine house, and look for more modest rented accommodation elsewhere in the

city. The move took place in 1660; Rembrandt, Hendrickje, Titus and Cornelia went to live in the Rozengracht, in a house that was at most only half as large as that on the Sint Anthoniebreestraat. Rembrandt had to start all over again.

But he went on painting, with the same dedication, with the same pursuit of something more and more striking, more and more true, with more and more concentration on the essence of the picture.