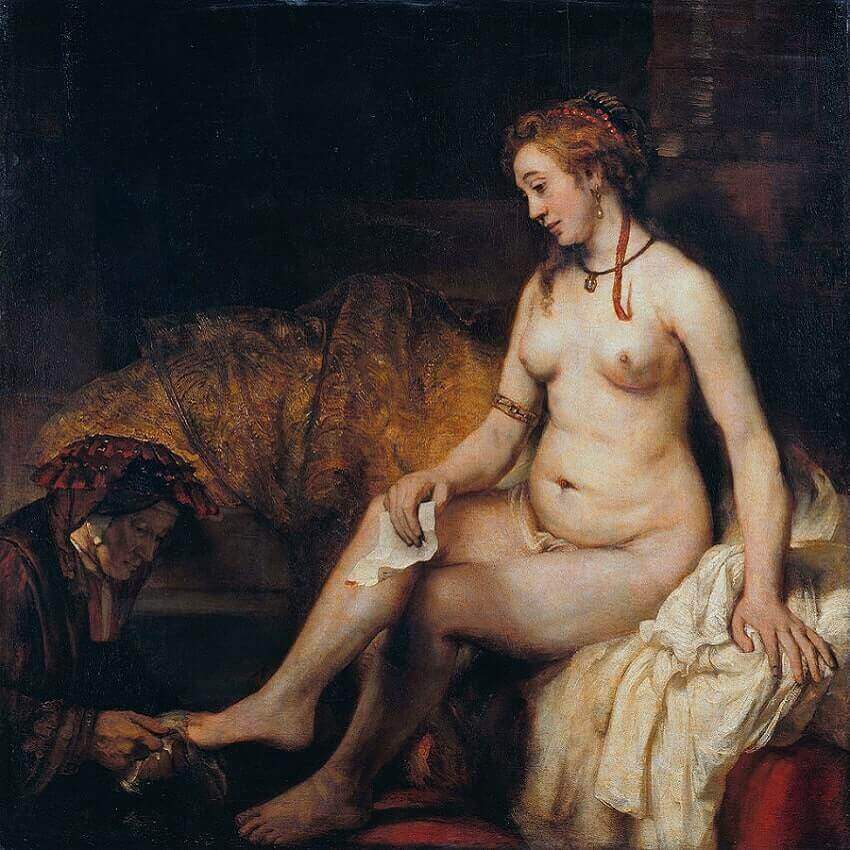

Bathsheba at Her Bath, 1654 by Rembrandt

From the roof of his palace King David once saw a very beautiful woman washing herself. Enquiring after the woman's name, and learning that she was Bathsheba, wife of Uriah the Hittite, David invited her to visit him, and lay with her.

Later he was to send her husband Uriah into the front line of battle where he perished.

Almost every painter who ever painted the story of Bathsheba chose the moment when David spied on her while she was bathing. But not Rembrandt in this case. His choice fell on the moment of Bathsheba's dilemma: should she obey the king's

command and that weighed heavily in those days - or should she stay faithful to her husband? From her troubled expression it looks as if she already senses the suffering that will result from her decision: the death of her husband,

God's reproaches which the Prophet Nathan would pour forth upon David, the death of the first child she was to bear David. X-rays have revealed that at first Bathsheba held her head up more confidently. Only later did Rembrandt choose to

make her bow her head in troubled contemplation.

Many drawings are known of naked women who had obviously modelled for Rembrandt and his pupils. Drawing nudes from a model was an important stage in a painter's education, and also for Rembrandt's pupils. These models were no ethereal beauties, but

ordinary Dutch women, who could make good use of the money they earned by posing. But Rembrandt also had prints in his collection after paintings by Italians, whose canvases usually represented women of ideal beauty. He put Bathsheba about halfway

between the two.

As so often, Rembrandt only indicated the setting in which the action took place, and did not show it in detail. The brilliant, gold-coloured bedspread is striking. Using a sophisticated technique, Rembrandt has us see that the bundle of white

linen on Bathsheba's left is a white sheet with a white shift lying upon it; the sheet is reproduced with thin, broad strokes, while for the shift the paint is applied more thickly and densely.

Rembrandt avoided anecdotal detail, so he showed David's letter face downwards. As such it contributes to the atmosphere of the painting. But Rembrandt knew how to show unmistakably that it was a letter: the folds in the paper can still be seen,

and one corner of the paper is curled up, so that the writing on it is visible.

The old serving woman is wearing an unusual large flat hat, covered with large loops of cloth, the sort of hat which in those days was used for the depiction of oriental women.