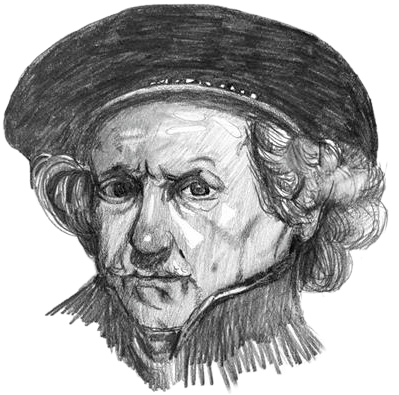

Self-Portrait, 1669 by Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt signed and dated this portrait clearly and in full, Rembrandt 1669, as he had been accustomed to do since the 1630s. It was to be his last self-portrait, and indeed almost his last painting. But there is no sign that his

powers are failing him, in his appearance, his technique or his signature. In September 1669 Rembrandt had had a visit from the painter Allaert van Everdingen and his son Cornells, who make no mention of sickness or the frailty of old

age. His death on 4 October 1669 must have been sudden. He was buried four days later in the Westerkerk; his coffin had sixteen bearers, which shows that it was no pauper's burial. The location of the grave in the church is not known.

Rembrandt was 63 when he died and had more than 40 years of painting behind him, in a life of much grief and adversity. His spirit remained unbroken to the end - or that is the kind of comment this portrait seems inevitably to provoke.

After his death an inventory was made of his belongings and effects in the house on the Rozengracht. Three rooms were sealed up and their contents not listed, since they contained Rembrandt's paintings and his art collection which

belonged, in accordance with the contract of 1660, to Hendrickje and Titus's company and were thus the property of their heirs, Cornelia and little Titia. This note in the inventory suggests that Rembrandt had again built up an art

collection in the second half of his life; unfortunately this time there is no record to tell what the collection contained.

The 1669 portrait is as surely and powerfully painted as the portraits of the 1650s. Rembrandt made only one later alteration, the gold-coloured stripes on the white cap, the better to make it harmonize with the finely painted

background, the grey hair and flesh tones of the face. Rembrandt's style of painting had lost nothing in quality. But the way he painted no longer suited contemporary taste. People wanted cool, evenly painted pictures of elevating

subjects, and that is precisely what Rembrandt's paintings were not. Nearly two centuries had to pass before Rembrandt was again widely recognised as a painter of genius, the painter who surpassed all his contemporaries. The recognition

would have pleased him. Had he not always striven to paint differently, better and with more perceptive vision than his contemporaries, yes, even to equal and surpass his famous predecessors?