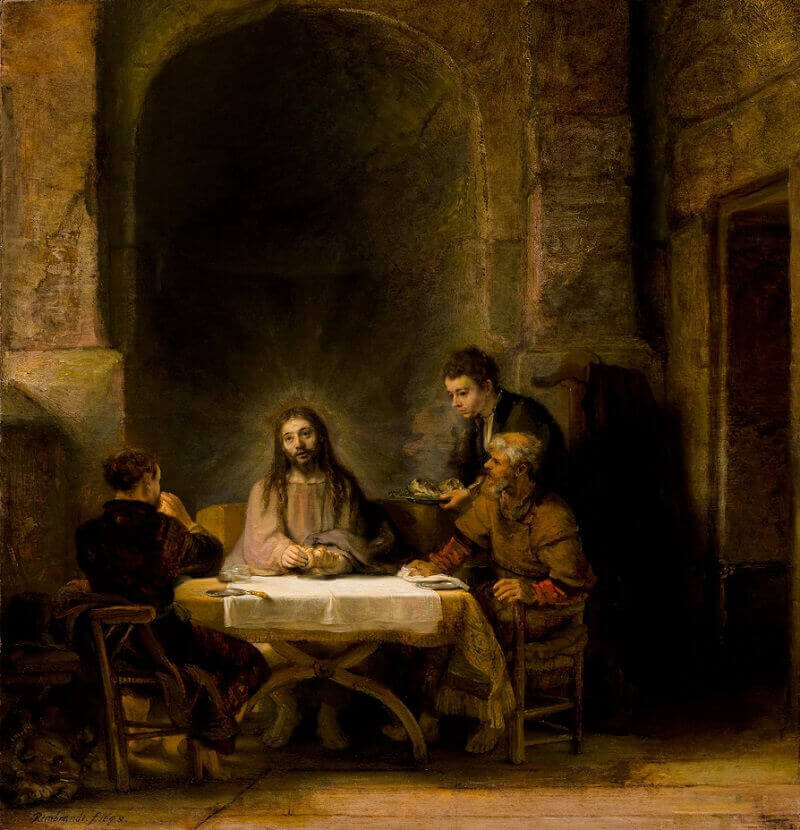

The Supper of Emmaus by Rembrandt

The Supper of Emmau is sensational. Literally a transformation of the knowledge conveyed by the senses; a transformation of the senses by knowledge. The extreme chiaroscuro is not there just as a cocky demonstration of

technique:"Caravaggio? Really. Now watch what I can get away with." The chiaroscuro is the subject. Light from darkness; the Scripture reconceived of as cure of blindness. The healer is

himself barely visible, seen in silhouette, the backlighting coming from some source immediately behind Christ's head, construable as some sort of candle but in every important respect declaring itself as the light of revelation,

the light of the Gospel.

Like nearly all Rembrandt's best pictures, the painting has insignificant but eye-catching imperfections. The big pouch or saddlebag hanging from a nail on the stone column seems stagily hung over the head of the googling

disciple, an analogue of the suspension of disbelief, inserted as the one passage of painting that lies in both light and darkness. But then this is, after all, a picture of suspense, and Rembrandt the stage director found

it impossible to resisi bringing together glittering still-life detail - the knife handle with its shining highlight projecting over the edge of the table; the white napkin - with the almost invisible figure of the second

disciple kneeling at Jesus's feet, the hair at the back of his head appearing to stand on end, and certainly to stand out against the white cloth, another reminiscene, in miniature, of the winding sheet of Passion. The

penumbra outlining the figure of the serving woman at the rear is needed to make her visible, and was presumably meant Rembrandt to suggest the light of the Gospel already working its illumination. But the effect is

disconcerting, a mild irradiation, like a watch face at midnight.