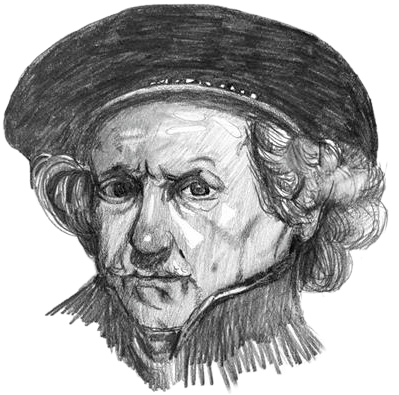

The Sacrifice of Isaac , 1635 by Rembrandt

Although at first sight Rembrant's version of The Sacrifice of Isaa in the Hermitage appears close to Lastman and Peter Paul Rubens, his alterations are strokes of pure theatrical

genius. Once again, there is manual performance at the center. The angel's right hand, painted in Rembrandt's most liquid smoothness, is laid on Abraham's enormous, darker paw, and instead of positioning Abraham's hand on

his son's head, a blindfold conveniently slipped to allow us to see the expression of Isaac's terror, Rembrandt turns the hand itself into a bandage, fully covering, indeed almost smothering, his son's face, at once a

gesture of tenderness and suffocating brutality. Between the hand-play, the sacrificial knife, on which Rembrandt has lavished his usual elaborate attention, hangs suspended in free fall, its blade still pointing at the

exposed throat of the helpless boy.

Rembrandt would have been as much aware as his Catholic predecessors (Caravaggio, Lastman, Rubens) that Christian tradition treated the sacrifice of Isaac as a prefiguration of the

later blood offering by the Father of His Son: the Crucifixion. Whoever commissioned the painting would have understood this subtext to be an important element in its devotional appeal. But as always, the challenge

Rembrandt set himself (and in this respect he was indeed truly the heir of both Caravaggio and Rubens) was not with abstruse confessional iconography- His work was to make sacred history credibly human. The test of a

father commanded to kill the son of his old age had horrible seriousness in a Calvinist.