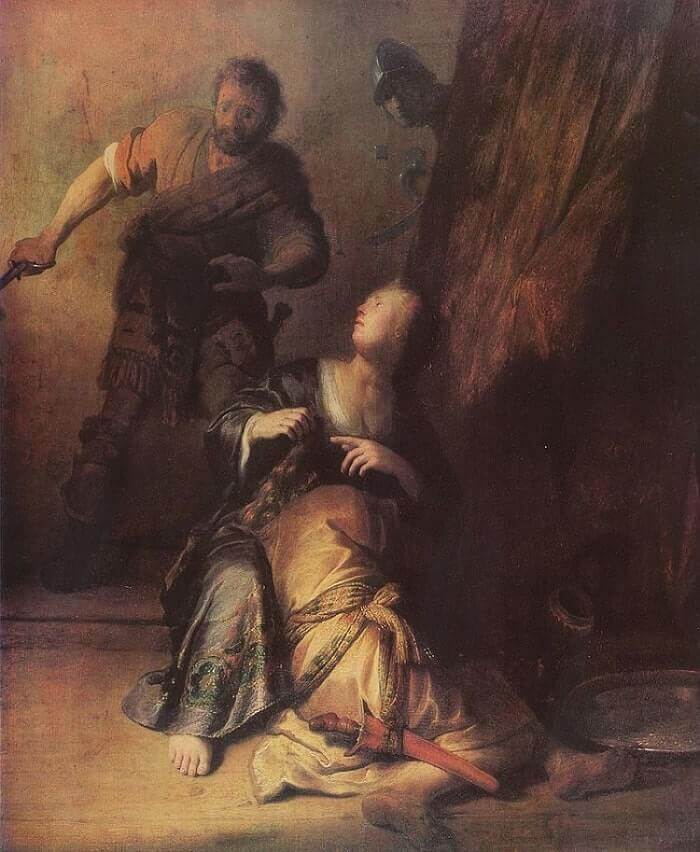

Samson and Delilah, 1629 by Rembrandt

Lastman remained an important source of subjects for Rembrandt's paintings in his later years, much as Lucas van Leyden was for his etchings. Yet within two or three years of studying with him, the young artist had clearly struck off on his own path, in collaboration with his contemporary Jan Lievens, also a former pupil of Lastman. Around 1625, the two artists worked closely together in Leiden and formed a relationship that was to prove an important spur to their creative imaginations.

Huygens accurately distinguished between the different sizes then favoured by the two artists, which are confirmed by their paintings. These also reveal that they shared certain subjects that were independent of their apprenticeship with Lastman, consciously extending beyond their master's range. The most notable of these is Samson and Delilah, the subject of one painting by Rembrandt and another one by Lievens of about 1628-30.

Both of the paintings depict the moment when Delilah, the sleeping Samson nestled in her lap, orders a Philistine to cut off his hair, depriving him of his strength. Lievens and Rembrandt depict the figures full-length, Samson and Delilah in the foreground and the Philistine advancing from behind, brandishing his shears. Although the order of these two paintings is unknown a comparison between them is an object-lesson in Lievens's more compromising approach to the theme and Rembrandt's utter incisiveness.

In the former Samson sleeps in an awkward and ungainly pose, his dangling arms and slumped back notionally recalling his strength; while Delilah, her hand to her lips, silences an approaching Philistine whose bulging eyes and stalking stance convey both his eagerness and trepidation. But Rembrandt eschews such posturing in favour of nail-biting suspense. Samson now slumbers in Delilah's lap like a child in that of its mother, no hint of his strength or beauty visible, only of his vulnerability. And Delilah no longer whispers but anxiously awaits as a Philistine stealthily approaches, another peering from a curtain behind. If Lievens's soldier appears startled by his sudden opportunity, Rembrandt's is summoned into action. Both may be posing, but only one is driven.