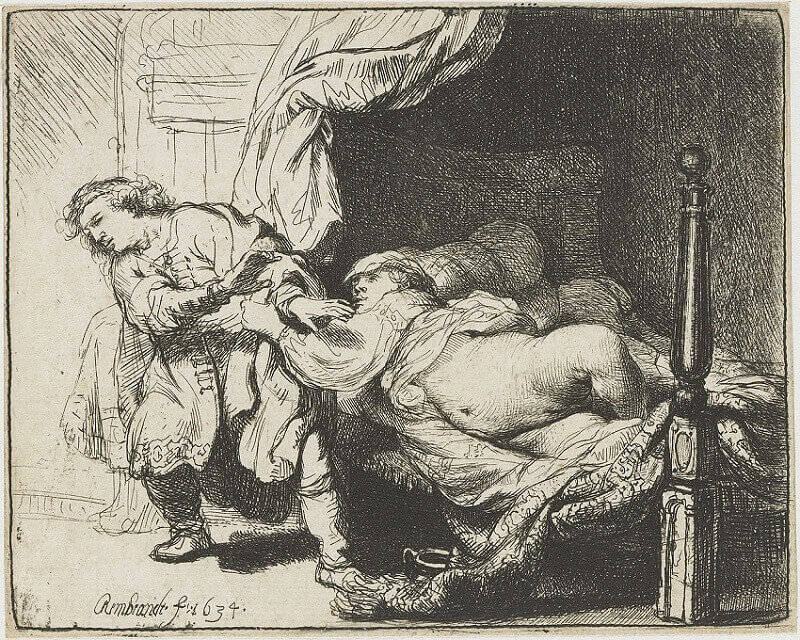

Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, 1655 by Rembrandt

To what extent the artist identified his own circumstances, and those of Hendrickje, with the story of David and Bathsheba will forever remain mysterious, but what can be established with certainty is that the transgression of marital vows remained an important theme in his art to the end of his life, for no other discernible reasons. In 1655, a year after Bathsheba, he painted Joseph and Potiphar's Wife showing Iempsar, Potiphar's wife, falsely accusing Joseph of having violated her before her husband when she in fact had tried and failed to seduce him (Genesis 39:6-13). This attempted seduction had already formed the subject of an early etching of 1634, which is one of the artist's frankest depictions of carnal lust.

More than twenty years later, however, Rembrandt turns from the physical temptations of the encounter to its moral results. Potiphar's wife now sits between her husband and her cowering, would-be lover, to whom she points accusingly while covering her breast in a gesture of proclaimed 'modesty'.

Although the biblical account does not mention the presence of all three figures, Rembrandt's depiction has convincingly been linked with an acclaimed production of a play on this theme by Joost van den Vondel staged in 1655 which included them all in a re-enactment of this scene. This larger cast of characters permitted the artist to explore all the ramifications of the story, much as he would later do in the Denial of St Peter. Like St Peter, Potiphar's wife here proclaims her innocence while inwardly guilty. In neither case are their 'victims' - Joseph or Christ - said to be present, but the inclusion of them underlines the gravity and consequences of the deception, and what need only have been a dialogue becomes a more well-rounded drama.